Can design carry a conversation beyond the walls of a lecture hall? Can it create richer context for the event itself? Can it spark new dialog and debate?

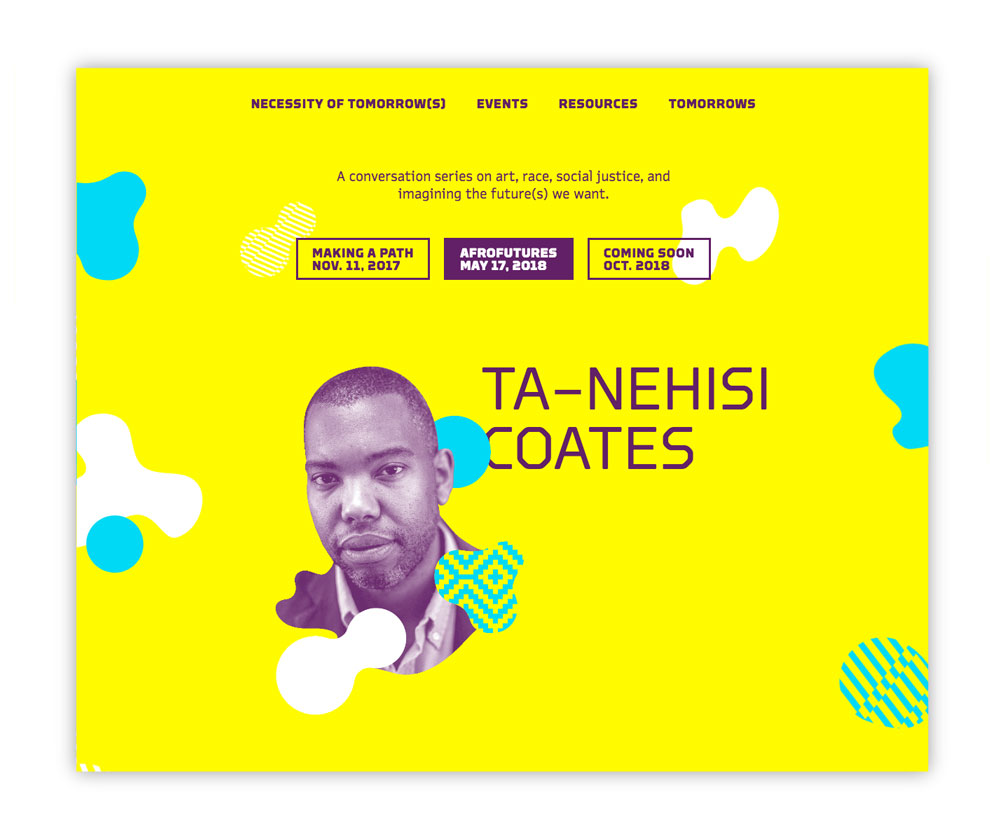

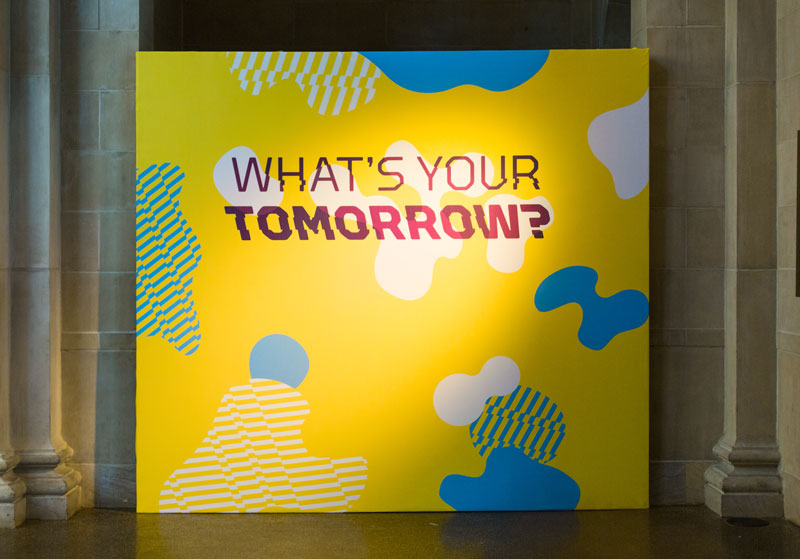

These were some of the questions we discussed with the Baltimore Museum of Art for The Necessity of Tomorrow(s), a high-profile BMA lecture series on art, race, and social justice, featuring prominent black artists like Mark Bradford, Ta-Nehisi Coates, and Boots Riley.

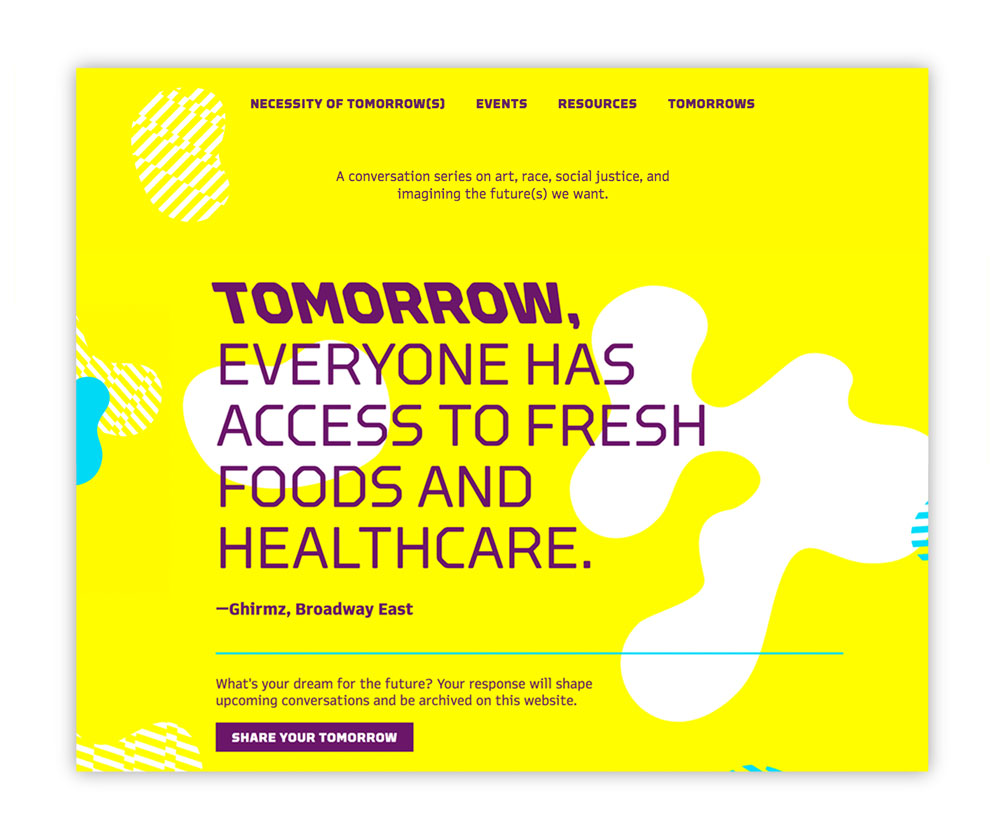

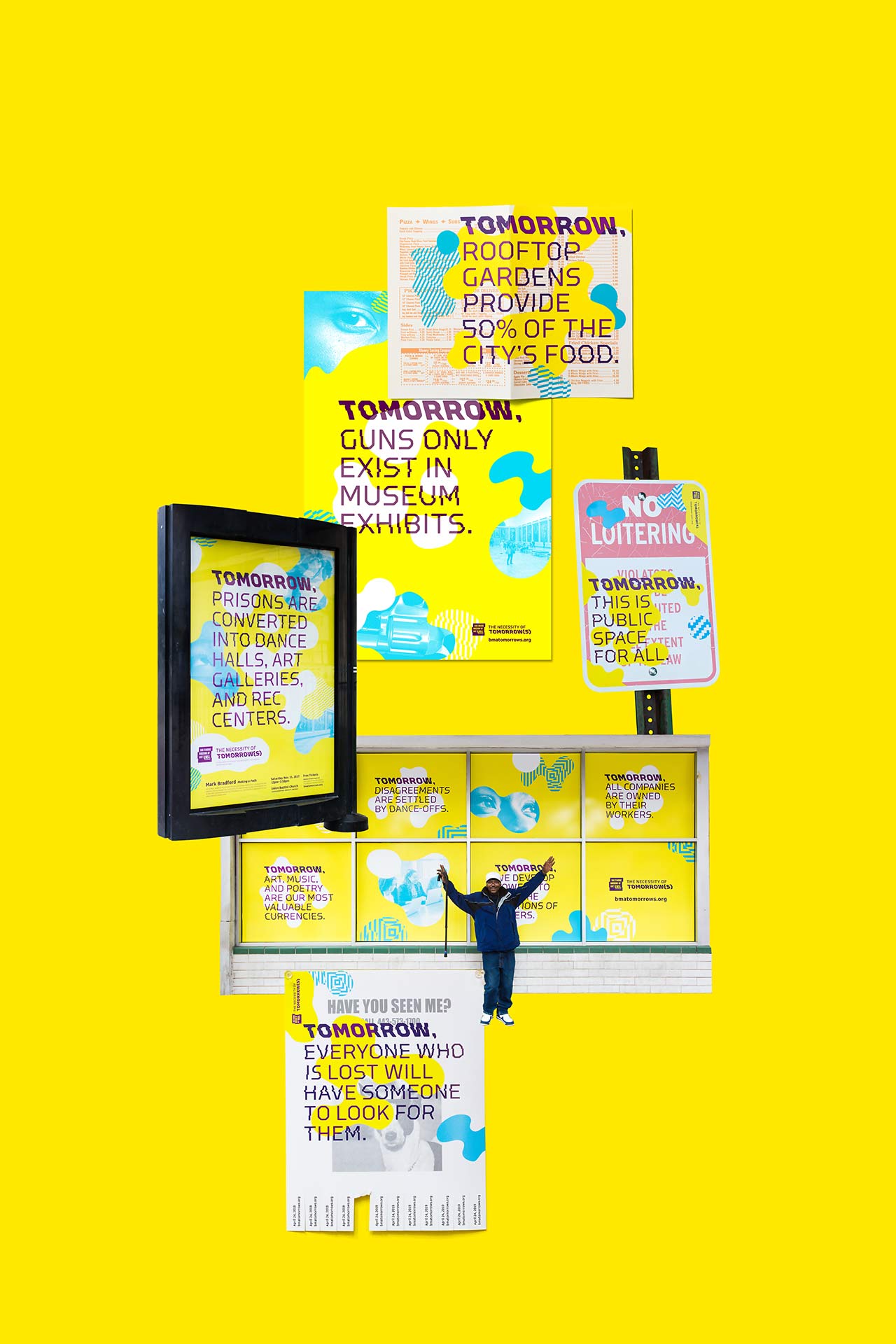

Language and ideas form the centerpiece of the promotional campaign, which incorporates radical, whimsical, and provocative visions of the future. These statements and others appeared on billboards, bus shelters, and posters around Baltimore over the course of several years.

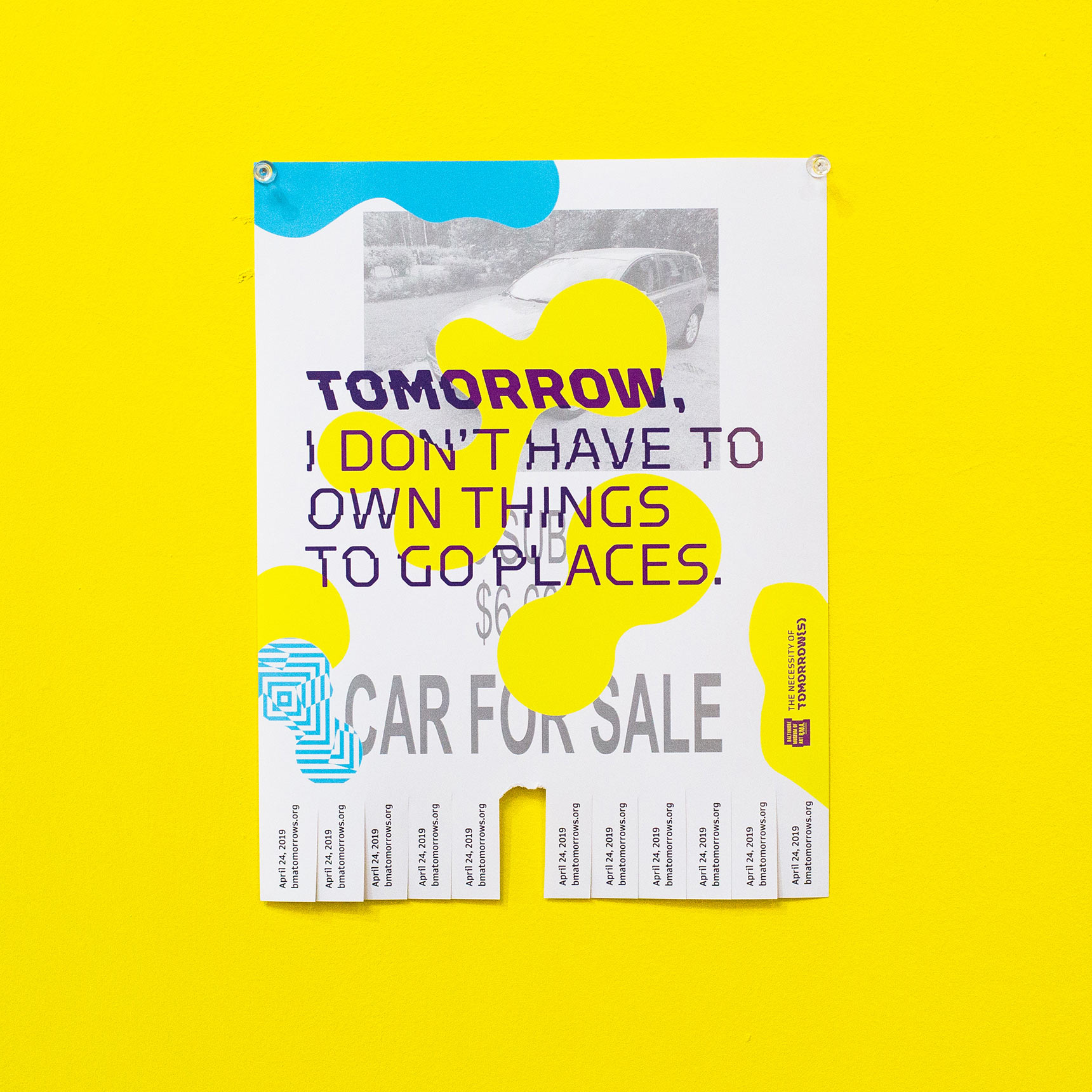

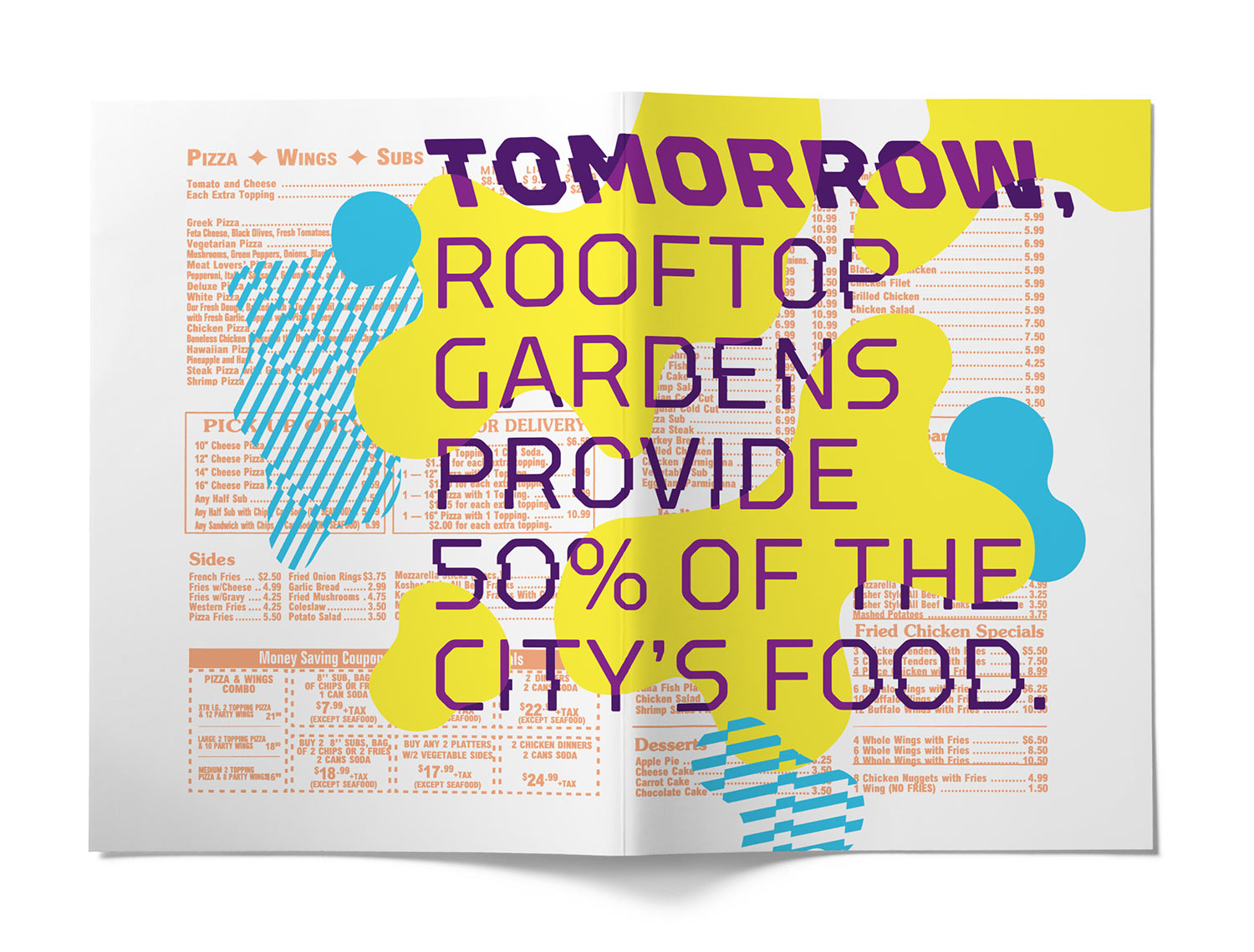

Part of the Necessity of Tomorrow(s) project includes a series of detournéments — public art interventions that interrupt vernacular advertising and signage with hopeful expressions of “Tomorrow…” By injecting these little surreal moments into the public realm, we aimed to spark further questions and conversations related to The Necessity of Tomorrow(s)’ themes.

Many of the signs and messages that surround us are designed intentionally to sell unhealthy products or perpetuate unhealthy systems. Interrupting them with unexpected, optimistic messages gives us a moment to turn a critical eye on these systems.

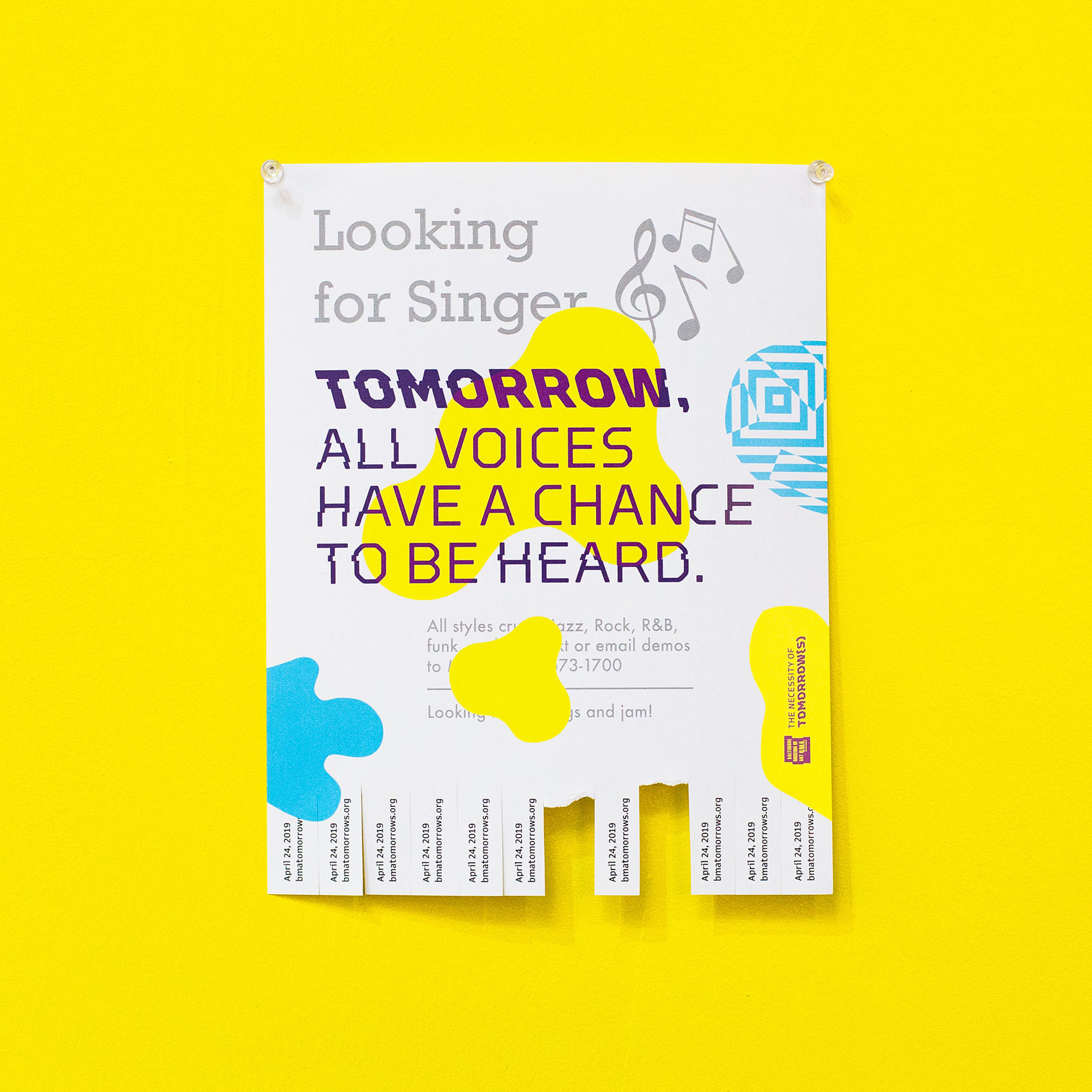

In 2019 we had the opportunity to create two temporary installations on vacant stalls at Lexington Market. For one of the installations we created a series of flyers layered with hopeful “Tomorrow…” messages.

A second stall at the Lexington Market installation featured posters and a comment box asking market visitors to share their visions for tomorrow. Community-contributed comments collected at the market, the Baltimore Museum of Art, and through the project website, helped to generate the ideas and language used in future stages of the campaign.

Engaging the community

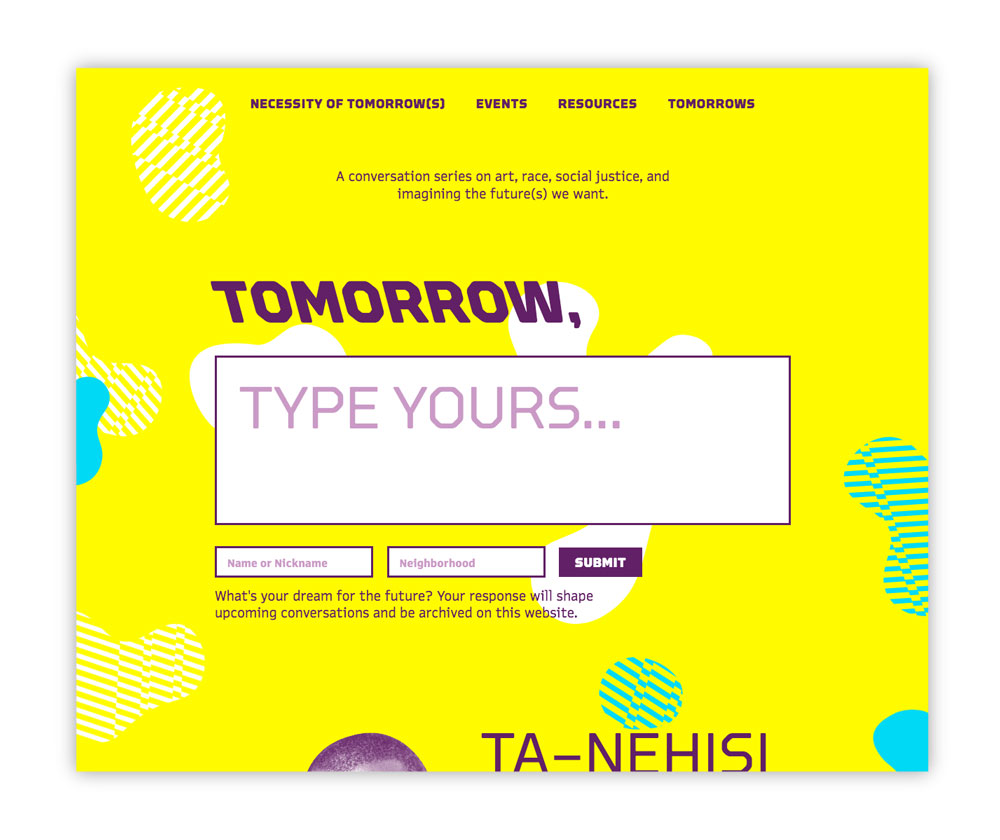

Participatory design plays a central role in the project. We asked Baltimore residents and BMA visitors to share their own visions for tomorrow through a series of feedback points on the project website, at the museum, and beyond.

Community contributions were archived on the project website and many of these helped inform the “Tomorrow…” language and ideas, appearing on later iterations of posters, advertising, and installations for the project. This participatory feedback and dialogue helped the campaign reflect a wider spectrum of ideas. And it supported our goal of carrying the conversations beyond the lecture hall and into the city.